COVID-19 may have taken the sting out of a potential no deal Brexit tale

‘No deal’ is not on many people’s Christmas list but, given cheap valuations for both equities and sterling, it may not be quite as disastrous for investors as some have suggested.

‘No deal’ is not on many people’s Christmas list but, given cheap valuations for both equities and sterling, it may not be quite as disastrous for investors as some have suggested.

As negotiations between the EU and UK drag on, a ‘no deal’ Brexit (trading on World Trade Organisation terms) once the transition period ends on 31 December is still a possibility. In spite of the Government’s reassurances that this outcome would cause minimal disruption, businesses and investors - fresh from the savage economic impact of COVID-19 - are understandably nervous. Perhaps a no deal Brexit should not be feared as much as the popular press would have you believe.

- First, COVID-19 has helped put Brexit in perspective. GDP dropped 19.8% in the second quarter, the worst performance since 1709, when the Great Frost caused chronic food shortages and destroyed the economy1. The short-term impact of a no deal Brexit is unlikely to be as severe. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) is currently estimating that a failure to reach a free trade agreement with the EU, ie, a no deal Brexit, will lower growth to 3.5% from 5.5% in 20212. It is very painful for the people involved but it is on a smaller scale than the collapse in economic activity from pandemic-related lockdowns.

- Second, the pandemic has also prompted vast monetary and fiscal stimulus. The Bank of England’s quantitative easing programme is currently equivalent to around 30% of GDP this year and next, compared to 9% during the 2007-08 Global Financial Crisis3. The OBR forecasts a public sector net borrowing of 19% of GDP, the biggest deficit since 19444. This policy easing should mitigate the short-term blow of any economic impact from a no deal Brexit. Ultimately, this debt must be repaid, with consequences for the tax burden on future generations, but that is a problem for another day.

- Third, the UK has become less reliant on foreign capital to finance economic growth. After the referendum in June 2016, the current account deficit was greater than 5% of GDP but it has since narrowed to 0.6% in the second quarter of 2020, its lowest level for 22 years, on the back of COVID-related depressed growth5. Nevertheless, given decades of running an external deficit, the UK has built up accumulated overseas liabilities and particularly those financed by the EU. Data from the Bank of International Settlements shows that the EU bank and non-bank financial claims on the UK total around £939bn, which compares to £587bn in UK claims on the EU6. Should the UK’s relationship with the EU turn acrimonious, there is a risk of EU capital repatriation from the UK. Given the relative size of these claims, any repatriation would likely involve larger net outflows from the UK than from the EU and therefore represent a risk for UK economic and financial asset performance.

It is unclear whether the UK economy is prepared for a potential no deal Brexit since the referendum in 2016. However, currency and financial markets have adjusted somewhat. Sterling has barely recovered any ground from its lows in the wake of the Brexit vote. On conventional measures of purchasing power parity, sterling looks undervalued and therefore less vulnerable to a sell-off. Other central banks are pursuing similarly aggressive monetary easing policies, so there is no pick-up in yield for buying, say, US dollars, as there was in 2016 when the Federal Reserve was raising rates. Sterling appears to reflect much of the negative news.

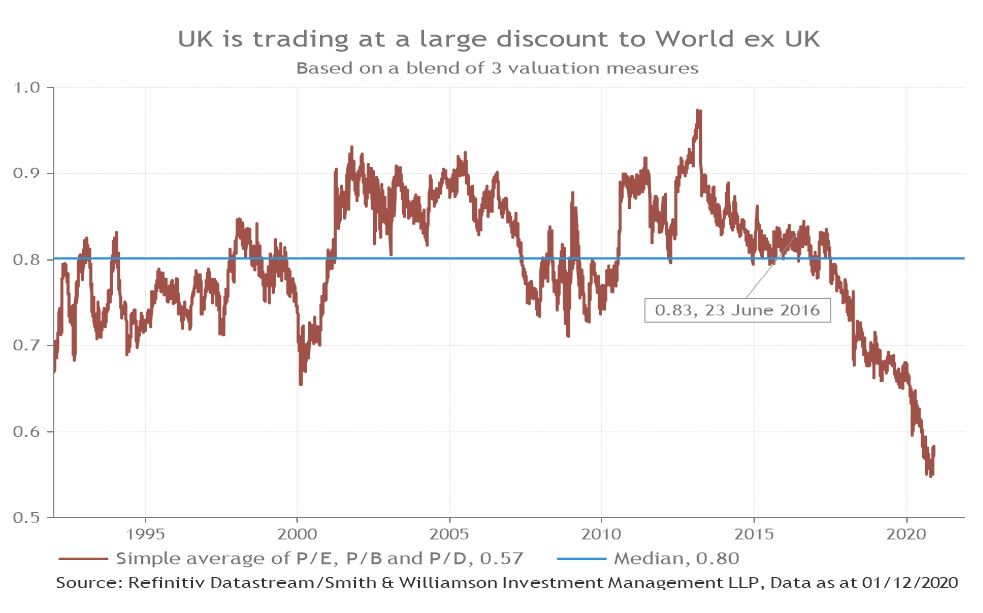

It is a similar situation with UK equities, which have significantly underperformed their international peers since 2016. They consequently look undervalued on almost any metric – price to earnings, price to book or price to dividend ratio. Combining these metrics as a simple average, the UK market is now 30% cheaper (relative to the world ex-UK) than it was at the time of the 2016 referendum (chart)7. This is partly because of its weighting to ‘value’ areas at a time when investors have been more focused on ‘growth’ equities but it is still the cheapest it has ever been. Even against a backdrop of quasi-lockdowns and no deal Brexit fears, it is telling that the MSCI UK benchmark gained 13.1% in November, its biggest rally in 30 years8. This suggests that much of the negative news associated with the UK has probably been discounted.

Of course, a no deal isn’t yet an inevitability. It is clear that amid his crowded inbox, US President-elect Biden is unlikely to prioritise a trade deal with the UK. He has expressed concern that the UK might compromise the Good Friday Agreement in the course of a no deal. Falling out with the EU is dangerous enough but falling out with the US at the same time – with a pandemic on – seems like a kamikaze approach. This may see British negotiators work a little harder to get a trade deal, to the extent that Morgan Stanley recently put the likelihood of the UK leaving on WTO terms at just 20%9.

These are precarious times for the UK but its difficulties are reflected in the price of its currency and stock market, which look historically cheap. ‘No deal’ is not on many people’s Christmas list but, given cheap valuations for both equities and sterling, it may not be quite as disastrous for investors as some have suggested.

References

1,3,7,8 Refinitiv Datastream, data as at 1 December 2020

2, 4 Office for Budget Responsibility – Economic and Fiscal Outlook, November 2020

5 Morgan Stanley, Policy Action Tracker – Focus Shifts To Fiscal, July 2020

6 Bank of International Settlements, data as at 30 November 2020

9 Morgan Stanley, Brexit and the US elections, November 2020

DISCLAIMER

By necessity, this briefing can only provide a short overview and it is essential to seek professional advice before applying the contents of this article. This briefing does not constitute advice nor a recommendation relating to the acquisition or disposal of investments. No responsibility can be taken for any loss arising from action taken or refrained from on the basis of this publication. Details correct at time of writing.

Risk warning

Investment does involve risk. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up. The investor may not receive back, in total, the original amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. Rates of tax are those prevailing at the time and are subject to change without notice. Clients should always seek appropriate advice from their financial adviser before committing funds for investment. When investments are made in overseas securities, movements in exchange rates may have an effect on the value of that investment. The effect may be favourable or unfavourable.

Ref: 165520lw

Disclaimer

This article was previously published on Smith & Williamson prior to the launch of Evelyn Partners.