Double trouble: Can the Eurozone economy ward off the dual shock?

The Russia-Ukraine series

Key messages

- This note takes a detailed look at the potential implications of the war for the Eurozone economy given its geographical and economic proximity to the crisis.

- Volatile energy prices and disruption in the financial sector have led to growing speculation amongst economists and market participants that the Eurozone could enter a recession this year. So much so that European equity markets are now pricing a sharp slowdown in growth.

- The magnitude and duration of the current energy crisis will depend on supply, demand, and the geopolitical risk premium applied by investors to energy. The geopolitical risk premium could fall if investors receive greater clarity on how the war will end. However, supply is constrained by geopolitics. Global demand for oil will be hit by higher inflation, slower global growth, and COVID lockdowns in China.

- Despite these challenges, oil and gas markets are in backwardation (i.e. participants in futures markets expect the prices to fall).

- The second main shock comes via the financial channel. We have already seen signs of instability in financial markets, with credit spreads widening and banking stocks underperforming the broader market.

- On the plus side, the direct exposure of Eurozone banks to Russia is limited. Some individual banks are more exposed than others, but those deemed to be systemically important have low direct exposures.

- Credit conditions have worsened but are not yet showing signs of stress. Corporate credit spreads remain far below the levels seen during the global financial crisis (GFC), the Eurozone debt crisis, and the pandemic.

- However, wild price swings in commodity markets have left some traders with sizeable losses on their positions. The collapse of a large commodities trading firm would have ramifications for financial stability.

- To estimate the economic impact of these risks, we model two scenarios for the Eurozone economy. In the base case, growth remains relatively strong over 2022/23, while inflation falls sharply next year, whereas the downside scenario sees a stagflationary environment over 2022/23. We do note, however, that these guideline forecasts are subject to major uncertainty given ongoing military developments, sanctions, and other policy responses.

- As we go to press, talk of a compromise between Russia and Ukraine lifted hopes that an agreement could be reached to end the war. This outcome would be constructive for markets, with equities responding positively to this news. It would also move the relative probabilities associated with our two scenarios in favour of the base case.

- Even if an agreement to end the war is reached, investors should continue to monitor the risks we have outlined. We expect there will be more twists and turns to come.

Market rebound? Not so fast…

2022 was meant to mark a fresh start for the Eurozone. Two years into the pandemic the economic area was expected to record strong growth amid higher fiscal spending and the full re-opening of economies. Indeed, at the time we thought that Eurozone equities would perform relatively well in this environment; particularly given that they were trading at low valuations compared to US stocks and the fundamentals — such as economic growth and corporate earnings — were showing signs of improvement. But as the build-up of Russian military forces on the Ukrainian border began to gather pace, investors started selling European assets as they worried about the spillover risks associated with a possible invasion. These fears crystalised on 24 February when the Russian President, Vladimir Putin, gave the go-ahead for Russian forces to invade Ukraine.

Clearly, the human consequences of this decision have been deeply distressing. Over the last couple of weeks, we have seen countless attacks on Ukraine including apparent targeting of the civilian population. It can seem crass to be commenting on financial markets at a time like this. However, it remains important that we, in our role as custodians, continue to monitor the risks associated with the war.

In our previous note, we outlined three main scenarios for how we thought the military action could unfold, as well as the potential market risks associated with these outcomes. In this follow up note, we take a more detailed look at the potential implications for the Eurozone economy given its geographical and economic proximity to the crisis. We focus on two main shocks — the energy crisis and the disruption in the financial sector.

What’s in the price? European equities are currently pricing an economic downturn…

As we mentioned previously, higher energy costs pose the largest direct risk to the Eurozone. The economic area imports over 90% of its energy, leaving it highly exposed to swings in the global market1. This is made worse by its dependence on Russia — 40% of the bloc’s gas and 20% of its oil comes from Russia, leaving it exposed to retaliation1.

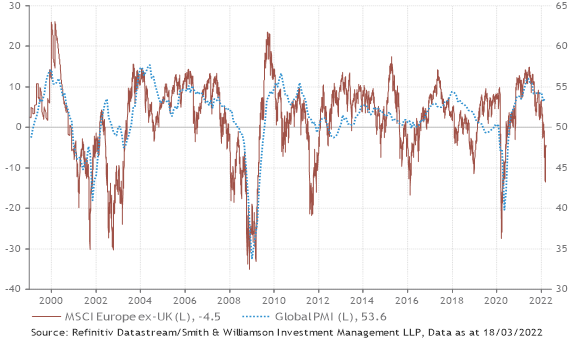

Volatile energy prices — and other spillover risks from the crisis — have led to growing speculation amongst economists and market participants that the Eurozone could enter a recession this year, so much so that European equity markets are now pricing in this possibility. The chart below shows the relationship between the global purchasing managers index, a measure of global economic activity, and the deviation of the current price of European equities from their 200-day moving average. Over the last two decades there has been a relatively strong relationship, which implies that Europe equities perform better than the 200-day moving average when global economic conditions improve. The recent negative deviation in European equities implies that investors expect economic activity to weaken.

Figure 1: MSCI Europe excluding UK (% deviation from 200-day moving average) and global Purchasing Managers index.

Will global economic activity fall sharply in response to the war? Or is the sell-off in European equities a knee-jerk reaction?

Shock 1: Energy market crisis

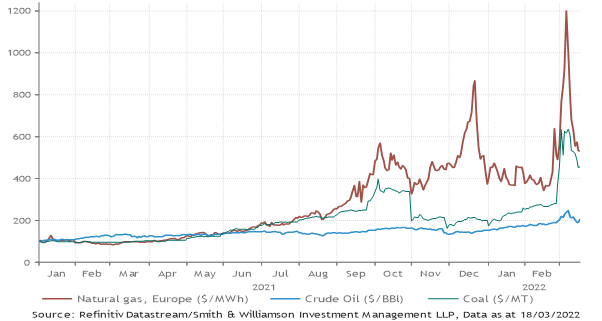

By now the oversized role of Russia and Ukraine in global commodity markets is well understood. Over the last month we’ve seen huge swings in the prices of oil, gas, and coal as market speculation that Europe and the US will ban Russian energy imports increased. While the US and UK have been able to follow through on this threat given their lower reliance on Russian energy, the EU has instead committed to reducing imports by two-thirds over the remainder of 2022. How it will manage this in practice remains to be seen. However, this greater certainty — in the near term at least — has helped bring crude oil and European gas prices down sharply in recent days. Looking forward, there are three main factors that will influence the outlook.

Figure 2: Energy prices have soared since the start of 2021 (Index set to 100 at Jan 21)

i. Ongoing geopolitical risks

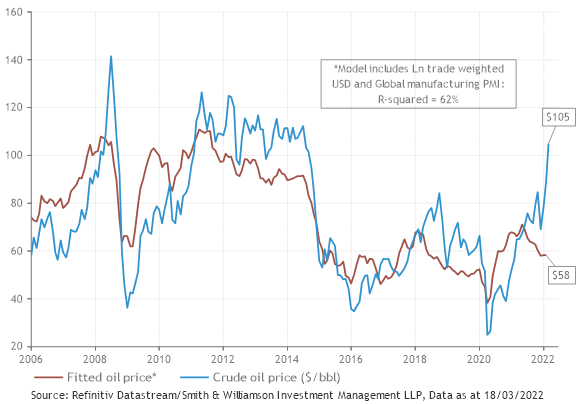

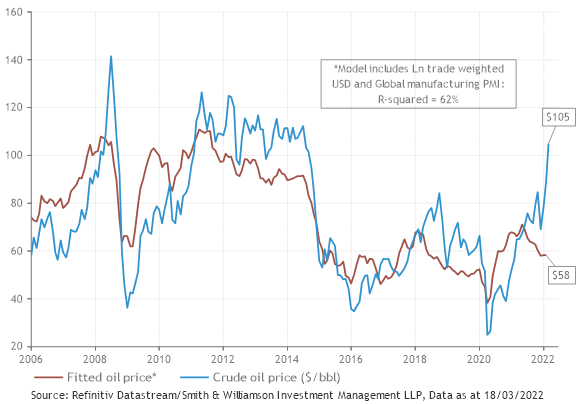

The first factor is the geopolitical risk premium assigned by investors to oil. This is the difference between how much investors are willing to pay for oil relative to the amount they should be paying if the asset remained unaffected by ongoing geopolitical risk. To estimate the current level of this risk premium, we built a simple econometric model to estimate the ‘fair value’ of oil — the price of oil based on the economic fundamentals, trade weighted USD and global manufacturing PMI. Our analysis finds that the current price of oil is around 50% above the price implied by the fundamentals2. Whether or not investors continue to assign this risk premium largely depends on how the conflict unfolds. The sharp price fall in recent days was driven by greater clarity on European energy policy. We expect the risk premium to remain volatile in the near term, unless investors receive more clarity around how the conflict is resolved.

With Russia providing around 40% of European gas imports, the geopolitical risk premium applied to gas is even higher. This explains the massive price swings we have seen over the last two weeks, with European gas trading between €80 per megawatt hour (p/mwh) and €300 p/mwh2.

Figure 3: Our econometric analysis finds that the geopolitical risk premium is adding 50% of the current oil price, fitted Brent crude oil price

ii. Supply is constrained by geopolitics…

The second factor relates to the economics 101 concept of supply. The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) March forecast suggests that demand will fall by 1.3 million barrels per day (mb/d) for the remainder of the year as the crisis weighs on global growth3. On the supply side, it estimates that from April, 3 mb/d of Russian oil output could be ‘shut in’ as sanctions take hold and buyers shun exports3. Moreover, the IEA reports that storage levels in OECD countries in January stood at their lowest levels since April 2014. All of this points to ongoing challenges on the supply side of the market.

However, this revised forecast remains subject to uncertainty. One key unknown is the extent to which the supply of Russian oil will be disrupted. While at this point Europe has refrained from a direct ban on Russian oil imports, concerns about sanctions and their implications have led many commodity traders to self-sanction. Indeed, Russian Urals crude has been selling at a 30% discount to Brent crude oil — with demand from India four times the 2021 average2. But further disruptions to European supply, through sanctions or retaliation, cannot be ruled out at this stage.

The second unknown is whether the global economy can replace Russian oil. In our view, it will not be easy.

US and UK sanctions on Russian oil mean that both economies have a gap to plug; the Eurozone will also be hit if Russian oil remains ‘shut in’. And despite the US being largely self-sufficient on energy, due to the shale boom of recent decades, low levels of investment means that this source is unlikely to make up shortages in the near term. Politically, this move back to carbon-intensive energy will be difficult for the Biden administration given its focus on net-zero transition, although his team has been speaking to shale producers in recent weeks to try and encourage greater output. To boost supply in the near term, the US agreed a deal with other IEA countries to release 60 million barrels from their emergency reserves (of 580 million barrels)4. Although this does not represent a large untapped source of oil — current estimates find that we are near record low levels of supply.

When we look further afield, more geopolitical challenges surface, and the supply dynamics do not get much better. To try and mitigate any potential shocks — and more importantly, the inflationary impacts on US consumers — the Biden administration has been reaching out to a series of petrostates. This has not been going particularly well. Last weekend, an attempt to reach a new nuclear agreement with Iran stalled, potentially reducing the chance of its oil coming back online to Western buyers. The US has even negotiated with Venezuela, which was banned from global energy markets in 2019 in a move against the Maduro regime. However, talks have yet to yield a firm agreement. Even if the US reached new agreements with Iran and Venezuela, this would not cover the expected disruption to Russian supply.

In fact, the IEA notes that only “Only Saudi Arabia and the UAE hold substantial spare capacity that could immediately help to offset a Russian shortfall”4. For now, it seems that both countries, along with their partners in OPEC, are sticking to their plan to gradually increase output through 2022.

Fewer geopolitical actors are involved in the European gas market: the impact will be shaped by what happens to Russian supply. Analysis by Algebris finds that Europe could cover up to 62% of energy needs tied to Russian gas from other sources — albeit at high economic and political cost5. This would still leave almost 40% unaccounted for. Policymakers would place household demand ahead of business demand, which could lead to industry shutdowns. The sectors most at direct risk include transport, metal manufacturers, and autos.

iii. Demand destruction?

The third leg is the demand side. Before the crisis, demand was expected to return to pre-pandemic levels in 2022. But the circularity of global markets could still throw this off course. Higher consumer price inflation resulting from higher energy costs could lead to demand destruction: there would be lower demand for oil because prices are too high. For the reasons we’ve mentioned above, the Eurozone economy is more at risk than the US. COVID-driven lockdowns in China could reduce demand further.

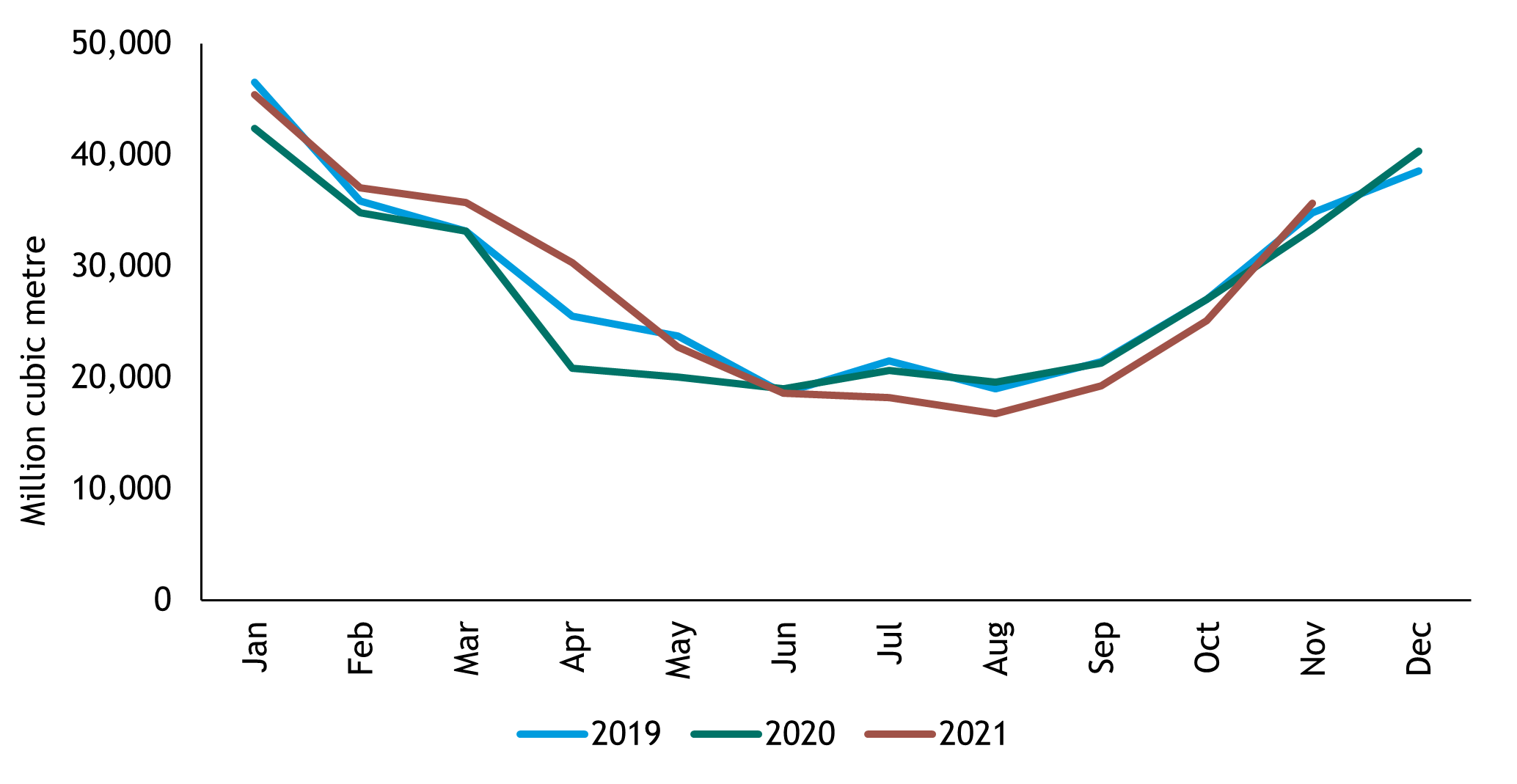

In the Eurozone, gas consumption will fall sharply in the coming months (see below figure), but that doesn’t necessarily mean that prices will fall. If prices return to €300 p/mwh, usage will plunge.

The bigger question is what happens next winter when higher demand returns? The Eurozone is now in a race to replenish its gas supplies and develop a more sustainable energy policy to meet the needs of future generations. In the short term, we could see greater use of fossil fuels to plug the gap. Over the medium term, Eurozone economies will bring forward green infrastructure expenditure.

Figure 4: Eurozone gas consumption is set to fall sharply in the coming months

Source: Eurostat, Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, data as at 14 March 2022

In summary, there are many drivers that will affect the price of oil and gas in the coming quarters and the outlook is unusually uncertain. Despite this, both markets are in backwardation (i.e. participants in futures markets expect the prices to fall). The market is expecting oil to come off its highs of over $100 to trade between $80-90 in the coming quarters2 and European gas prices are also expected to fall. Given this uncertainty, we model two different price profiles in our analysis of the Eurozone economy (see final section).

Shock 2: Financial sector disruption

The second main shock hitting the Eurozone comes via the financial channel. We have already seen signs of instability in financial markets with credit spreads widening and the underperformance of banking stocks. A large part of this instability has been driven by the sanctions placed on Russia in response to the invasion. The exclusion of several Russian banks from the SWIFT messaging system, which is seen as the plumbing of the global financial system, has been particularly damaging. This means they can no longer transact with major foreign financial institutions. It has also limited Russia’s ability to use its large foreign exchange reserves, which had been accumulated to support the domestic economy in times of crisis. However, this also has consequences for the West and allies, making it difficult to purchase Russian energy, and leading to volatility in commodity markets.

Our analysis considers three additional ways in which the crisis is impacting the Eurozone financial sector.

i. The direct impact on Eurozone banks should be manageable

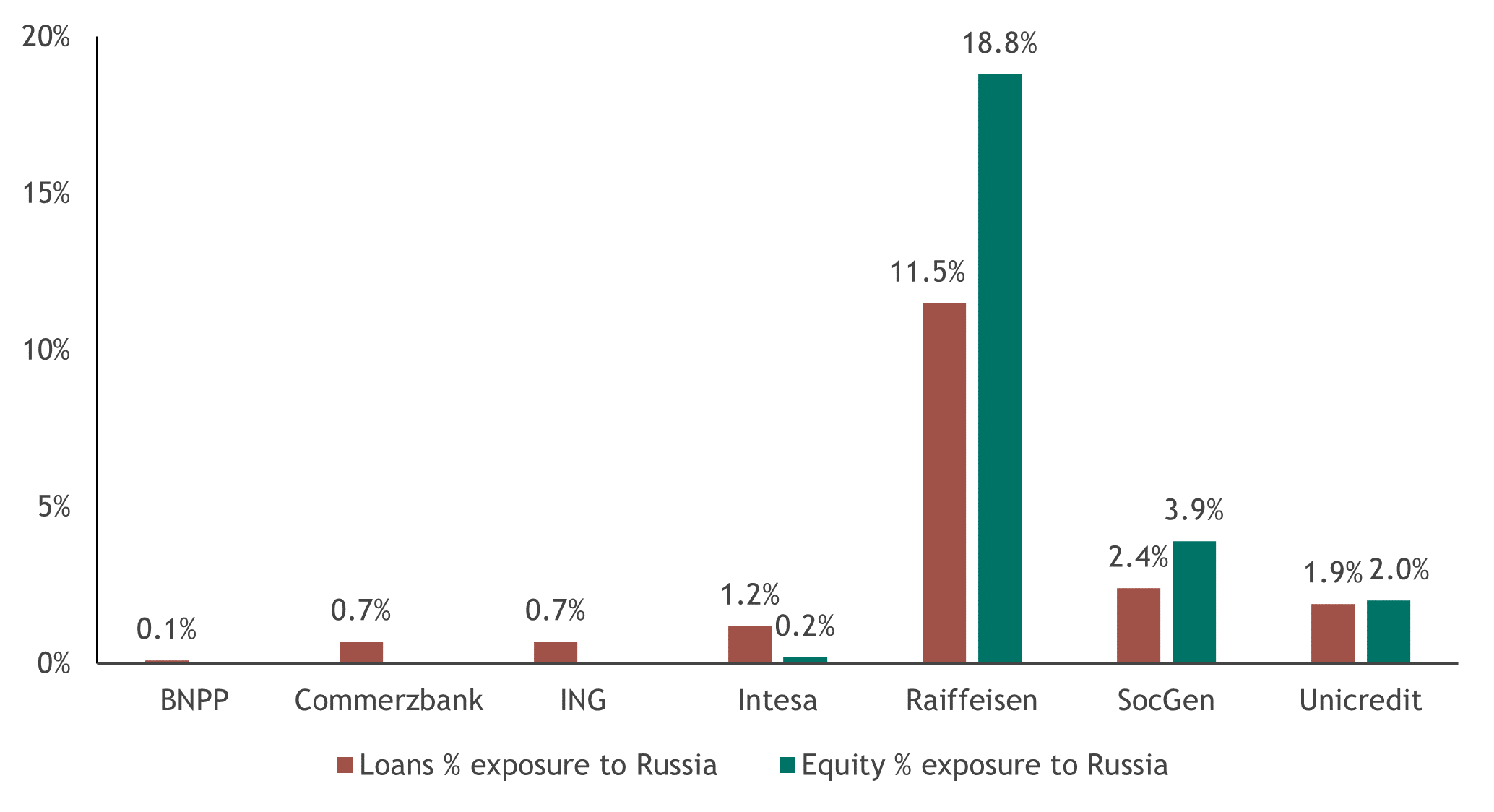

On the plus side, the direct exposure of Eurozone banks to Russia is limited. Some individual banks are more exposed than others, but those deemed to be systemically important have low direct exposures.

The figure below shows the Eurozone banks with the highest levels of exposure, measured by loan and equity exposure to Russia as a share of group assets. Raiffeisen, an Austria bank, is most at risk. It will likely incur write-offs on its Russian subsidiaries, which will hit its Tier 1 capital ratios — a measure of financial health. However, the overall impact is expected to be manageable given its overall funding position.

Of the systemically important banks, Société Générale (SocGen) has the largest exposure. However, with a Tier 1 capital ratio of 13.7% (470 basis points above the 9% level required by regulators), the bank has stated that it has “more than enough buffer to absorb the consequences of a potential extreme scenario”6.

Figure 5 Eurozone loans and equity exposure to Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus (% group)

Source: UBS/Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, data as at 31 December 2021

In our view, the greater risk to the Eurozone banking sector comes from the potential hit to growth resulting from the crisis. Banks are more profitable in stronger economic environments, and the potential for lower growth presents a sizeable downside risk. Particularly as the economic environment had looked set to improve in 2022.

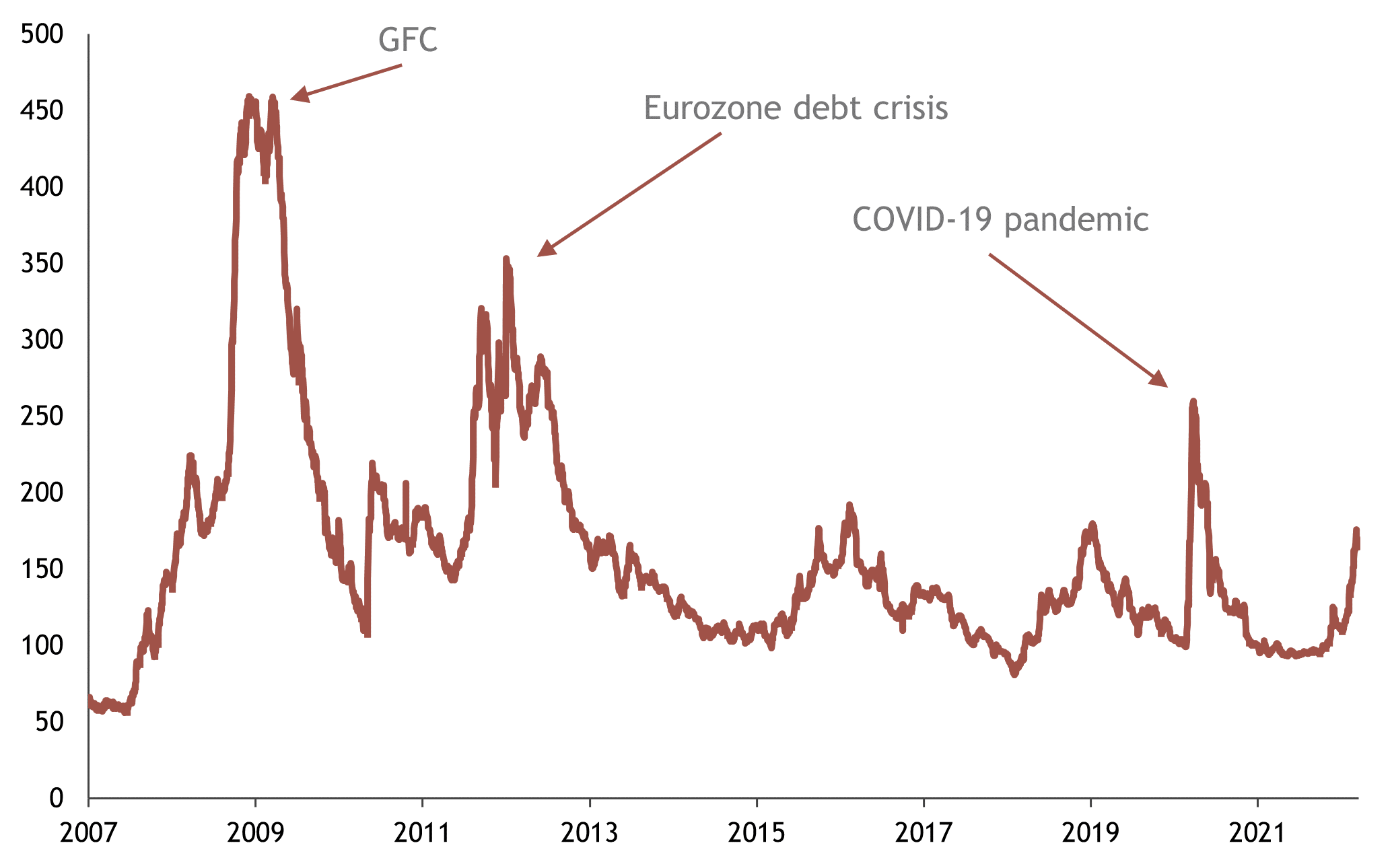

ii. Credit conditions have worsened, but are not yet showing signs of stress

Eurozone credit spreads, which measure corporate credit risk, have increased. Despite this, spreads have only reached the average level seen over the last 15 years, which implies that investors currently view the risks to be relatively contained. Spreads remain far below the levels seen during the global financial crisis (GFC), the eurozone debt crisis, and the pandemic.

Figure 6: Euro corporate credit spreads have spiked, but remain below previous crises

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, data as at 18 March 2022

The spreads on Eurozone banks’ credit default swaps (CDS), which effectively act as insurance against a borrower default, remain similarly contained, again implying that investors perceive the sector to be resistant to the shock.

iii. Derivatives contracts could still unravel

The third potential avenue of financial disruption brings us back to the energy sector. Recent disruption in energy — and broader commodity markets — has meant that market makers are finding it increasingly difficult to provide liquidity.

This is complicated by the fact that derivatives contracts are widely used in commodities trading to hedge against risks. The wild price swings seen in recent weeks have left many commodity traders with huge losses on these contracts. This could force some traders to default on these contracts, which would then have knock-on implications for firms exposed to the trade. Consequently, firms could withdraw from the market because the risks are too great, reducing liquidity in the market and further exacerbating the problem.

In a bid to avoid this situation, the European Federation of Energy Traders have written to European policymakers to ask for short-term liquidity support. As they weigh up this request, it seems that existing losses do not yet pose a systemic threat to financial markets. However, if one of the major trading houses were to get caught up in the turmoil and collapse, it could present a problem for the global economy.

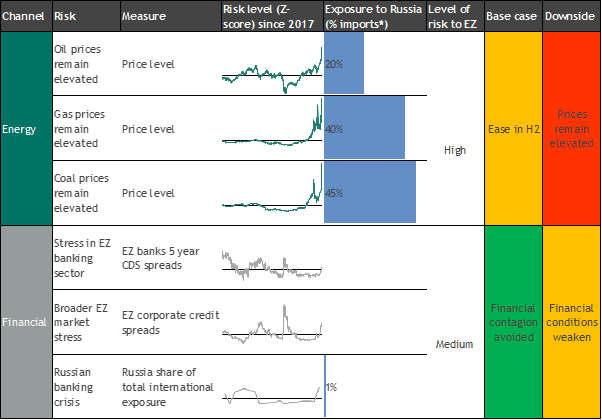

We are monitoring these shocks through our risk framework

While there are many risks emanating from the war, we’ve focused our analysis on what we view as the two main risks impacting the Eurozone: elevated energy prices and financial sector disruption. The table below brings this together into our Eurozone risk framework. For each risk measure we calculate Z-scores for the last five years, to see how the measures have evolved over time. The table shows that compared to the financial measures, the energy measures are significantly higher across the board, highlighting the greater threat posed by risks in the energy sector.

We also consider the relative risk exposures to Russia. For energy this looks at dependency on Russian imports. For financial risks, we consider the amount of assets held by European banks in Russia as a share of total international assets. Again, these measures show that the energy sector is more exposed to Russia than the financial sector.

The final two columns outline our view for how these risks may pan out over the second half of 2022 and into 2023. Clearly, there is significant uncertainty around these forecasts. Our base case view is that oil and gas price should ease from their recent highs of $130 per barrel and €300 per megawatt hour. We also expect the Eurozone to avoid a significant deterioration in financial conditions.

To account for the significant uncertainty around these views, we outline a downside scenario. This sees energy prices remaining elevated and financial conditions weakening as stresses in financial markets spill over to the real economy.

Table 1: Energy and financial risks are the key channels we are monitoring

Source: Refinitiv, BIS, Eurostat, Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP

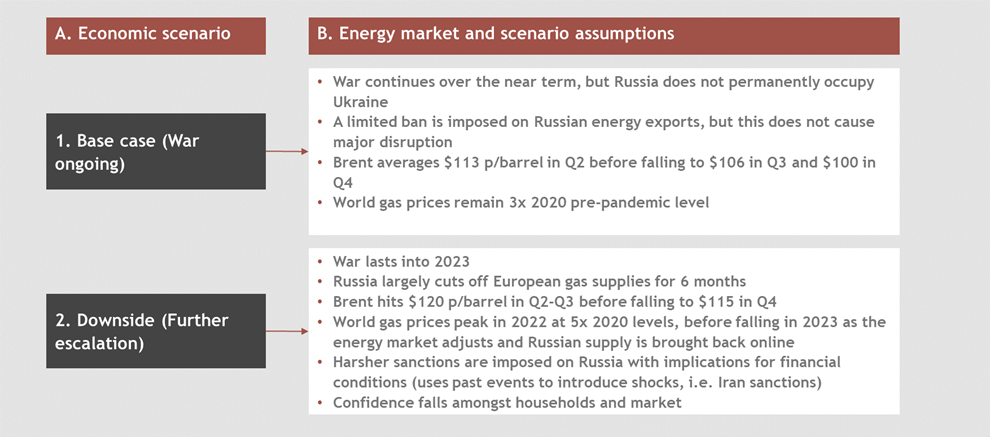

To estimate the economic impact of these risks, we model two scenarios

Our first scenario assumes that the war continues over the near term, but there is not a permanent occupation of Ukraine. This sees energy prices remain high compared to 2021 levels, but easing in the second half of 2022 as the market gains more clarity on how the conflict may end.

The downside scenario sees the hostilities last for the remainder of 2022 and into 2023. In response to further Western sanctions, Russia significantly reduces European gas supplies over a six-month period. This escalation in tensions leads to higher energy prices across the global economy, which hits Eurozone consumption and reduces economic growth.

Figure 7: Overview of modelling scenarios

Source: Oxford Economics Global Economic Model, Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP

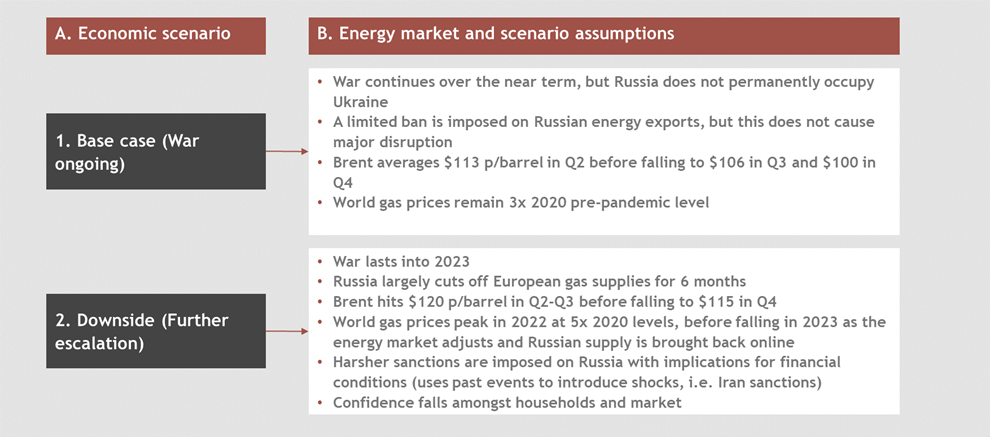

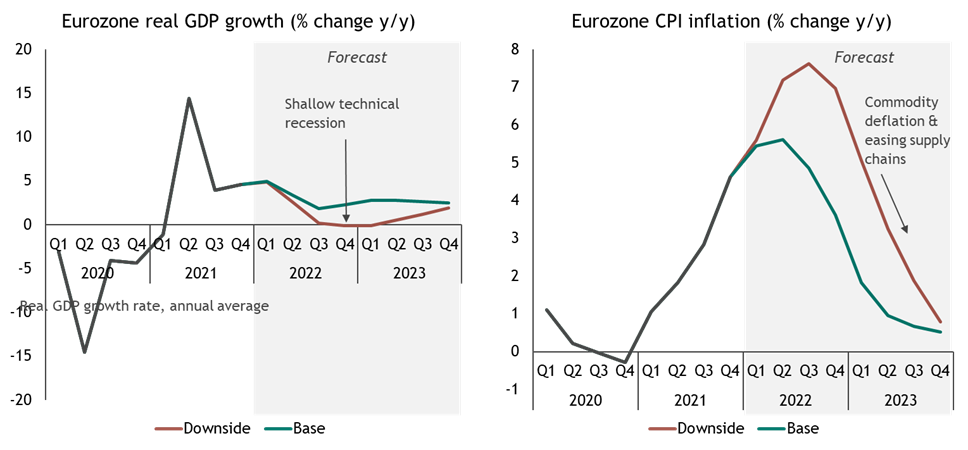

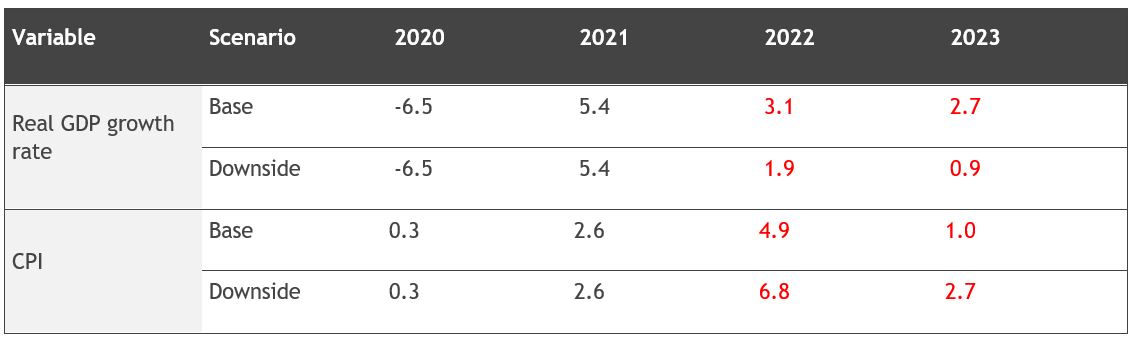

Using the Oxford Economics Global Economic Model, which consists of over 26,500 interlinked equations based on econometric analysis and economic theory, we model these scenarios to understand the implications for the Eurozone. This analysis finds that growth in the base case scenario comes in at 3.1% for 2022, almost 1% lower than the pre-invasion estimate of 4%7. Under the downside scenario, the Eurozone enters a technical recession (two-quarters of negative growth) with growth remaining weak into 2023.

From an inflation standpoint, Eurozone CPI peaks around 5.5% in the base care before falling in 2023 as improving supply chains and lower commodity prices contribute to disinflation7. The downside scenario sees inflation peak around 7.5%, as energy prices remain elevated into 2023 due to ongoing tensions7.

Overall, this analysis suggests that under the base case assumptions, growth will remain relatively strong, and inflation should fall sharply next year. Whereas a downside scenario could see the Eurozone enter a stagflationary environment over 2022/23. We do note, however, that these guideline forecasts are subject to major uncertainty given ongoing military developments, sanctions, and other policy responses. The risks remain skewed to the downside, and there is, of course, a small chance that a significantly worse downside scenario plays out than the one modelled here.

Figure 8 and 9: Eurozone real GDP (% change YoY) and Eurozone CPI (% change YoY)

Source: Oxford Economics / Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, data as at 14 March 2022

Table 2: Real GPD growth rate and CPI, annual averages (red indicates forecasts)

Source: Oxford Economics / Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, data as at 14 March 2022

Producing forecasts is difficult at the best of times…

As we go to press, talk of a compromise between Russia and Ukraine lifted hopes that an agreement could be reached to end the war.

This outcome would be constructive for markets, with equities responding positively to this news. It would also move the relative probabilities associated with our two scenarios in favour of the base. If an outcome like the base case occurs, we think that Eurozone equities will bounce back from the recent sell-off. A large chunk of the EU COVID-19 recovery package kicks in this year, while increased energy spending and excess consumer savings provide further tailwinds.

But if the downside scenario materialises it will be increasingly important to be selective when picking stocks. Some sectors perform better than others in stagflationary environments.

Even if an agreement to end the war is reached, investors should continue to monitor the risks we have outlined. We expect there will be more twists and turns to come.

The next note in our Russia-Ukraine series will consider how global equities perform in different economic environments, including the ones outlined here.

Sources:

1 Eurostat, 18 March 2022

2 Refinitiv Datastream, 18 March 2022

3 IEA (2022), Oil market report, 16 March 2022

4 IEA, “IEA member countries to make 60 million barrels of oil available following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine”, 1 March 2022

5 Algebris Investments (2022), Europe Unplugged: can we give up Russian gas?

6 SocGen, “Update on the group’s current situation in Ukraine and Russia” 3 March 2022

7 Oxford Economics, 15 March 2022

i) A z-score measures a given value’s deviation from the mean. 0 (shown by the horizontal line) indicates a value equals the mean. A positive score indicates that the current value is above the mean, and vice versa.

Important information

This document is solely for information purposes and is not intended to be, and should not be construed as investment advice. Whilst considerable care has been taken to ensure the information contained within this commentary is accurate and up-to-date, no warranty is given as to the accuracy or completeness of any information and no liability is accepted for any errors or omissions in such information or any action taken on the basis of this information. The opinions expressed are made in good faith, but are subject to change without notice.

You should always remember that the value of investments can go down as well as up and you can get back less than you originally invested. Past performance is not an indication of future performance.

Issued by Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Financial services are provided by Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP and other companies in the Tilney Smith & Williamson Group, further details of which are available at www.tsandw.com/compliance/registered-details. © Tilney Smith & Williamson Ltd 2022.

Ref: 220311300

Disclaimer

This article was previously published on Smith & Williamson prior to the launch of Evelyn Partners.