Geopolitical risks under a Biden administration

The pandemic prompted a hiatus in geopolitical tensions, as governments turned inwards to deal with the crisis. However, the easing of restrictions has reopened some old wounds. US/Russian relations have soured, while Israel and Palestine have resumed their long-running conflict. China has resumed its geopolitical ambitions by agitating in Taiwan. Should this trouble investors?

The pandemic prompted a hiatus in geopolitical tensions, as governments turned inwards to deal with the crisis. However, the easing of restrictions has reopened some old wounds. US/Russian relations have soured, while Israel and Palestine have resumed their long-running conflict. China has resumed its geopolitical ambitions by agitating in Taiwan. Should this trouble investors?

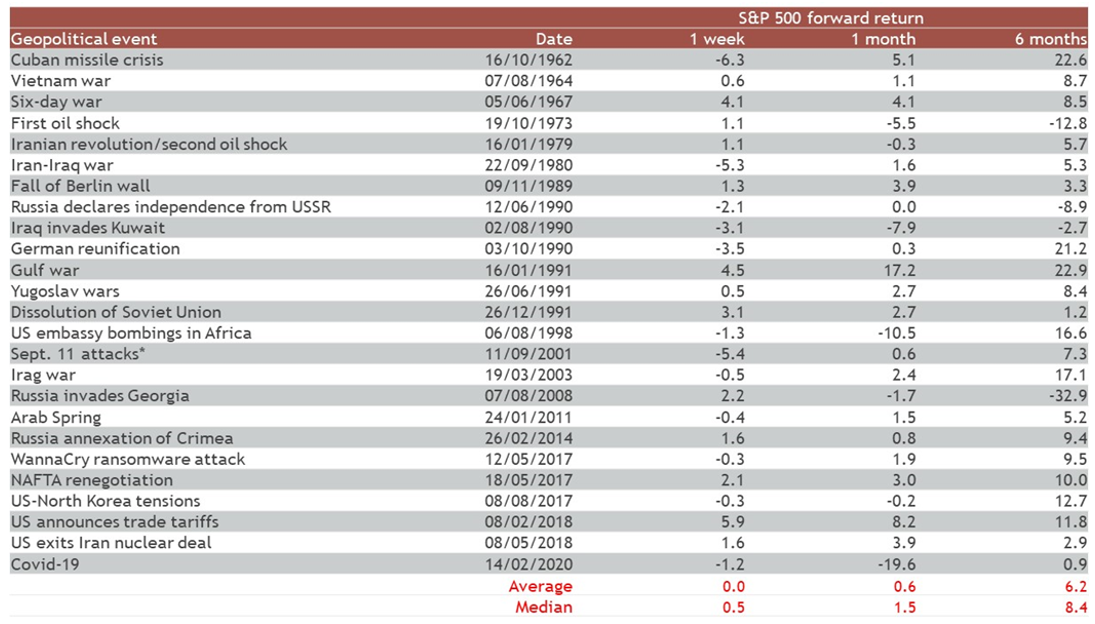

History suggests that the investment consequences of rising geopolitical risks are generally short-term. While there is often a short-term hit to markets, it is usually followed by a speedy recovery. The allegedly North Korean WannaCry ransomware attack in 2017 prompted a 0.3% fall in the index, but after six months, the market was 9.5% higher. It is a similar picture for the September 11 attacks, the Arab Spring or, even, COVID-19 (chart 1).

Chart 1: Equity corrections from post-WW2 geopolitical risk (ex-oil supply events) tend to be short-term in nature

Source: Bloomberg/Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, Data as at 12/05/2021

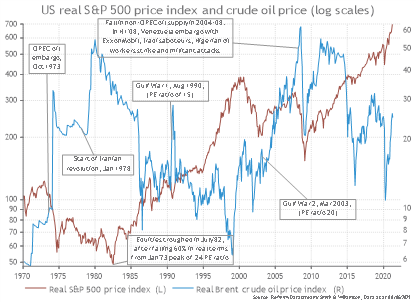

Geopolitical disruption in markets tends to endure if it effects a sustained decrease in oil supply. This was most evident in 1973, when the US stock market had taken a 12.3% hit six months after the first oil price shock. The resulting spike in energy prices led to a long period of accelerating inflation during the rest of the decade. In real terms, US equities fell 60% from a peak in December 1972 to a trough in July 1982, when inflation eventually showed signs of peaking after the Fed tightened monetary policy aggressively (chart 2).

Chart 2: The 1970s oil shocks had a major impact on US stock prices

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, Data as at 03/06/2021

In contrast, when Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, this had a lesser impact on equities. That’s because of the expectations that the US-led coalition would end the Iraqi occupation and avoid a sustained disruption to oil supply. The bottom line is that provided oil keeps running, markets appear to be able to shake off geopolitical tensions. Indeed, the Iraq war in 2003, for example, saw a small fall in the S&P 500 (0.5%), but six months later, the index was 17.1% higher.

It remains to be seen, however, whether in future, this might shift – with areas such as the metals needed for renewable energy infrastructure or even water access becoming important battle grounds. ‘Chip wars’ may also be a driver for geopolitical tensions.

Joe Biden faces three key foreign policy tests

Geopolitical risk will probably involve the US in the future and particularly, as military rivals, like China and Russia, may “test the mettle” of a new incoming US president. As the US president slowly puts the pandemic behind him, Joe Biden faces three key policy challenges: Russia/Ukraine, Iran/Israel and China/Taiwan. The problems are complex and long-running but will only spill over into markets in certain circumstances.

Rising tensions with Russia over Ukraine

It is in Russia that tensions appear to be high. In this State of the Nation address on 21 April, President Putin warned the West against crossing Russia’s “red lines”, while Biden condemned Russian interference in the US election, saying “efforts to undermine the conduct of free and fair democratic elections” constituted an “unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy and economy of the US”.

A key stress point for US/Russian relations centres on the Ukraine. On 24 March, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky signed a decree that approved the "strategy of disoccupation and reintegration of the temporarily occupied territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the Sevastopol city." Essentially, the Ukraine showed its intention to bring back the Crimea into the Ukraine, after Russia used the opportunity of political chaos in Kiev to annex the region in 2014.

Russia responded to this threat from the Ukraine to take back the Crimea on 15 April by closing off the Kerch Strait to all foreign warships (not commercial/trade vessels) until October. This narrow stretch of water, which connects the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, is an important link between southern Russia and "annexed" Crimea. The US then stepped in on the same day to ban US banks from buying new Russian sovereign debt (effective on 14 June).

Nevertheless, there are some hopeful signs: Putin and Biden have agreed to meet at a summit in Switzerland in June. Russia declared it would withdraw its roughly 100,000 troops from the Ukrainian border. While the Biden administration is officially attempting to halt the final leg of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline – which would connect Germany and Russia under the Baltic Sea and avoid using the Ukraine’s pipeline network to provide natural gas to Europe - it has not yet put America’s full weight into stopping it. In fact, last month the Biden administration waived sanctions on the company and CEO building the controversial pipeline and indicates that the US is not willing to compromise its relationship with Germany over the project. This creates a bizarre situation where ships involved in the construction of Nord Stream 2 could face US sanctions, but not the company in charge of the overall pipeline!

De-escalation is not certain, however. Some US officials have cast doubt on Russia’s withdrawal of troops from the Ukraine. The Belarus situation could also inflame tension between the region and the West. Russian domestic politics remains unsettled. Putin’s approval rating still lingers in a relatively low range. The economic recovery is weak with a general election due in September. These domestic troubles may encourage Russian political leaders to stir up trouble abroad.

Brokering a nuclear deal with Iran

Talks between the US and Iran are re-starting, paving the way to the US re-joining the 2015 nuclear deal from which it withdrew in 2018 under President Trump. Tensions are likely to remain high during negotiations. The closer the US and Iran get to a deal, the more Iran’s opponents (i.e. Israel) will need either to take action or make preparations for the aftermath. Israel will certainly underscore its red line against nuclear weaponization and has already been implicated in the sabotage of Iran’s Natanz nuclear facility on 11 April.

There have also been other outbreaks of violence. A US coast guard ship fired warning shots as a group of 13 Iranian fast boats moved towards US navy vessels in the strait of Hormuz in May1, while an Iranian tanker was hit by a drone at a Syrian oil terminal. It is possible that tit-for-tat attacks over the next few months could have repercussions for oil supply.

While US-Iran diplomacy appears to be on track according to media reports, there will be bumps in the road. There is also the added problem of the Iranian presidential election. The current presidential incumbent Rouhani cannot run due to term limits and hardliners are expected to win. Biden will be looking to close a deal before the new president is inaugurated in August.

Should a nuclear deal with Iran be agreed, it would allow the country to export more crude oil into the energy market. Data from Bloomberg show that Iran oil exports in May were just 0.1 million barrels a day (mpd), well below a previous peak of 2.5m before President Trump imposed unilateral sanctions against the country in 2018. A nuclear deal would also encourage Saudi Arabia and Russia to increase oil output or risk losing market share to Iran. The bottom line is an Iranian oil deal could limit the post-pandemic upward trend in energy prices putting upward pressure on consumer inflation, a key market risk for equities.

US/China/Taiwan

The most market-sensitive source of geopolitical risk may come from the China/Taiwan relationship. China continues to see Taiwan as part of its territory, but Taiwan feels very differently. The dispute goes back more than a century, but China has been upping its military activity in Taiwan in recent months2. Taiwan is crucial to China because of its expertise in chip-making. Chips are crucial for China’s technical and environmental ambitions, but the US has cut China off from its semiconductor industry at a time when there is already a worldwide shortage.

If the US pursues a full technological blockade then China may take tougher action on Taiwan. The administration is due to release a licensing process for companies concerned about US export controls on the technology trade with China shortly.

BCA Research puts the odds of a China/Taiwan crisis at 60% over the next 12-24 months, but only a 5% chance of full-scale war3. It says that China will strive to avoid war because of the damaging economic effects, but the odds may rise in the event of domestic Chinese instability, a game-changing US arms sale, or a Taiwanese declaration of independence.

China and the US continue to be at loggerheads. While Biden is a different style of president to Trump, his views on China are not fundamentally different. The US and China are escalating their naval confrontation in the South China Sea, particularly around the Philippines. There are tensions over technology know-how, trade and global leadership.

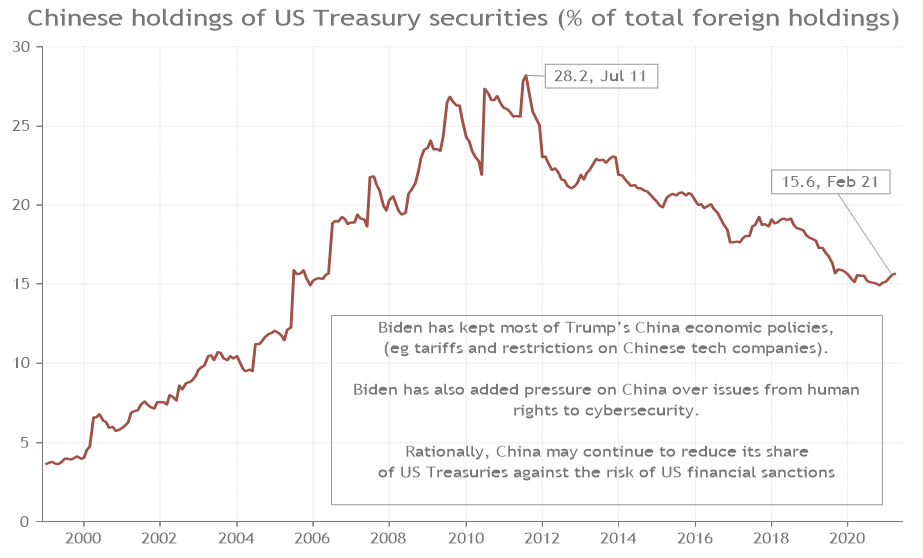

Arguably, a key investment message is that, provided geopolitical tensions between the US and China do not spill over actual conflict, geopolitical tensions are likely to exert downward pressure on the US dollar. That’s because China is likely to recycle less of its trade surplus into US Treasuries for fear of US financial sanctions down the road (chart 3).

Chart 3: Sino-US tensions add to downward pressure on the US$

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, Data as at 08/06/2021

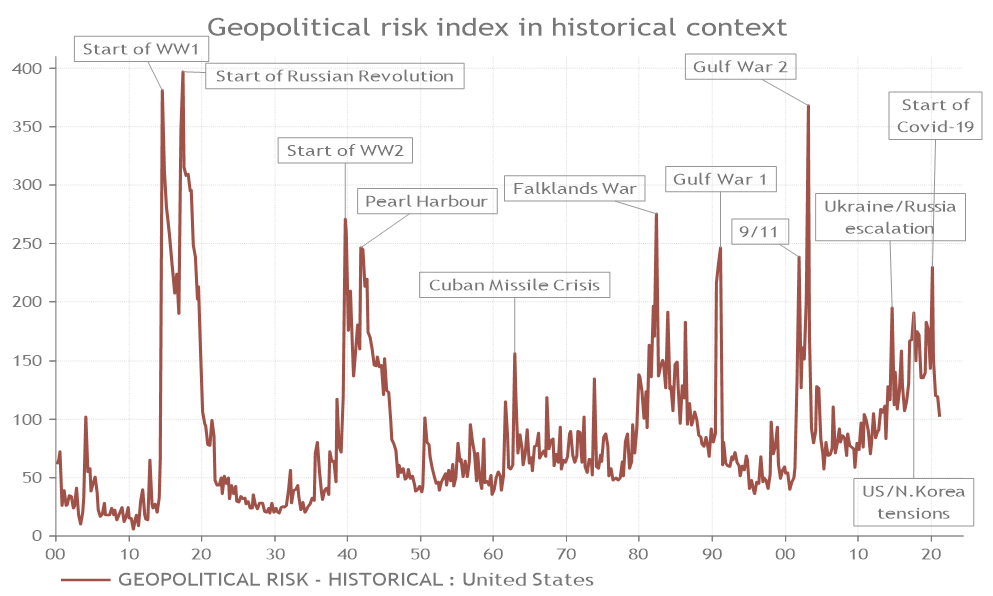

To summarize, geopolitical risk is reviving as governments start to look outwards once again in a post-pandemic world. Investors, in general, are unprepared, with benchmark measures of geopolitical risk (using media sources for words that reflect conflict) at historic lows (chart 4). However, our analysis suggests that it takes a lot to rattle markets. Disruptions to resources and political communications are key to determine if geopolitical risks will spill over into affecting financial and currency markets. BCA concludes that if the US, China, Russia, and Iran choose “jaw-jaw” over “war-war” then the global equity rally will see another leg up.

Chart 4: Geopolitical risk appears to have eased during the pandemic

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, Data as at 08/06/2021

Sources:

- The Guardian, US ship fires 30 warning shots after Iranian vessels approach fleet 10 May 2021

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/may/10/iran-navy-us-coast-guard-warning-shots - BBC News, What’s behind the China-Taiwan divide, 26 May 2021 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-34729538

- BCA, Jaw-Jaw or War-War?, 16 April 2021

DISCLAIMER

By necessity, this briefing can only provide a short overview and it is essential to seek professional advice before applying the contents of this article. This briefing does not constitute advice nor a recommendation relating to the acquisition or disposal of investments. No responsibility can be taken for any loss arising from action taken or refrained from on the basis of this publication. Details correct at time of writing.

Risk warning

Investment does involve risk. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up. The investor may not receive back, in total, the original amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. Rates of tax are those prevailing at the time and are subject to change without notice. Clients should always seek appropriate advice from their financial adviser before committing funds for investment. When investments are made in overseas securities, movements in exchange rates may have an effect on the value of that investment. The effect may be favourable or unfavourable.

Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP is part of the Tilney Smith & Williamson group.

Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority

© Tilney Smith & Williamson Limited 2021

Ref: 75421eb

Disclaimer

This article was previously published on Smith & Williamson prior to the launch of Evelyn Partners.