Human capital is indeed capital

COVID-19 crisis brought human capital into the spotlight for investors. Human capital is one of the essential assets a business needs to produce the goods and services it sells. It is also an important determinant of the value of companies’ intangible assets and hence of their overall value.

One of the side effects of the Covid-19 crisis has been to bring human capital into the spotlight as one of the few variables capable of playing a key role, first in protecting the economy and society and second, in maximising the chances of a rapid output recovery when the pandemic ends. But, before briefly discussing recent events, it may be appropriate to look at the concept of human capital in some detail.

What is human capital?

There is no rigorous definition of human capital. It is a loose term that is generally considered to be the sum of several factors, notably the knowledge, skills, and abilities of employees.1

Human capital is thus to be regarded as one of the essential assets a business needs to produce the goods and services it sells. Unlike most other assets which are physical in nature (such as land, plant and equipment) human capital is intangible, and hence particularly difficult to value. Nonetheless, it often represents a large share of the overall value of a company and can play a significant role in the determination of its long-term success or failure. Patents, copyrights, intellectual property, goodwill, brands, trademarks and research & development are other examples of intangible assets, but they all rely on human capital in one way or another. In short, human capital is indeed a form of capital, both for companies and for the economy as a whole: with physical capital, technology and institutions2, human capital is one of the basic forces driving the economy and providing better standards of living.3

Why human capital matters for investors?

Since the late twentieth century, there has been a transition from an industrial economy to a knowledge economy – a transition largely fuelled by rapid technological progress.

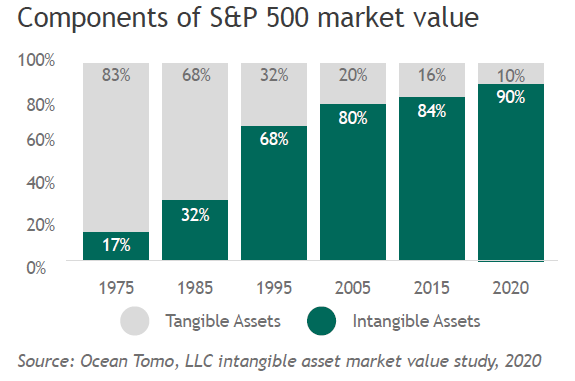

The knowledge economy has been defined as “a system of consumption and production that is based on technology and the knowledge acquired by the workers”.4 It relies increasingly on human capital and other intangible assets, rather than on physical capital and natural resources as in the industrial economy. While precise figures are still not available, for developed countries the knowledge economy is generally believed to generate a large, if not the largest, share of gross domestic product (GDP). The long-term growth of intangible assets relative to tangible assets in the US economy is clearly shown in the chart. Over the last 45 years, the percentage of the market value of the S&P 500 firms represented by intangible assets has surged by more than fivefold, from around 17% in 1975 to around 90% in 2020, according to estimates of the investment advisory firm Ocean Tomo5.

Equivalent data for European markets cover a much shorter period. The proportion of intangible assets in the market capitalisation of the S&P Europe 350 companies has also increased, although at a slower pace, from 71% in 2005 to 74% in 2020, according again to Ocean Tomo6. These figures largely reflect the importance of big tech firms "FAAMGs"7in the US economy relative to Europe.

The bottom line is that investors assessing the value of firms must pay close attention to the human capital of these firms, which is likely to be an important determinant of the value of their intangible assets and hence of their overall value.

How can the value of human capital be increased?

Given the rapid pace of technological progress mentioned above, to preserve and improve their human capital it is essential that companies provide more and better training and retraining to their employees. This is likely to set off a positive chain reaction boosting employees’ commitment and productivity, product and service quality, customer satisfaction, sales volume, profitability, and ultimately stock market valuation. While empirical evidence has confirmed such a correlation, more research is needed to establish the direction of causality.8 This may be a classic chicken and egg dilemma: did superior financial performance arise because of better trained employees, or did the company have more funds to invest in training because of a good financial performance due to other factors?

How can valuable employees be prevented from leaving?

The skills that make up human capital belong to the individual employees, not to the company. When employees leave the company, they take their knowledge, skills, and abilities - clearly a damaging outcome for the company. To prevent it, companies have to adopt a holistic approach that covers all aspects of the work environment and that will enable them to retain their employees. This includes a long list of measures, such as competitive remuneration packages and attractive career opportunities, applying best practices in health and safety, and having strong equal opportunity and workplace diversity programmes, as well as provisions for health and wellbeing, and flexible working hours. Companies that use employee engagement surveys (especially where there is a large workforce) are better able to identify and react to areas of concern among workers, while also giving employees a sense that management is committed to their welfare. A wider use of such policies would be beneficial to most companies.

How is human capital treated in the investment process at Smith & Williamson?

Human capital comprises an integral part of the investment process.

For many sectors, including technology, healthcare, financial services and media, human capital is one of the most important ESG factors. It is likely to play a major role in the assessment of the value and prospect of companies in these areas since these companies tend to require a large workforce of highly skilled individuals.

But human capital is systematically monitored for all companies and is focused on how companies attract, develop, and retain employees while providing working conditions favouring greater employee engagement. For that, Smith & Williamson notably looks at staff share programmes and remuneration, equal opportunity and workplace diversity programmes, training programmes, knowledge-sharing processes, employee satisfaction on Glassdoor (a website where current and former employees anonymously review companies), overall employee turnover, as well as health and safety policies and performance. Also considered is whether companies are performing employee engagement surveys or similar processes.

As already noted, companies that perform well in this respect are likely to be more resilient and able to attract talented employees, and hence to remain competitive and thrive. On the other hand, poor human capital management is likely to lead to higher employee turnover, lower employee productivity, higher costs and a loss of competitiveness which may threaten the very existence of the company.

The Covid-19 crisis and human capital

As noted in the introduction, the Covid-19 pandemic has greatly increased the interest in human capital.

A vivid example of this was the initiative in March 2020 of a group of more than 280 large investors with $8.2 tn assets under management (AUM) to call on companies to protect their workforce and their communities, as countries all over the world were imposing the first lockdowns9.

At first sight, this call may appear contrary to normal practice, as the majority of investors are said to focus on short-term results and expect shareholder primacy – a principle divesting corporate directors of any responsibility other than to maximise profits for their shareholders. In fact, the investors behind the call, while recognising the considerable challenges posed by Covid-19, urged companies to do their best to prioritise safety, the use of paid leave and the maintenance of employment relationships. These measures were aimed at protecting society at large and the companies in which the investors have invested from potentially very harmful outcomes. These investors acknowledged the importance of human capital as an asset, and that by protecting it companies stood to be well rewarded when the economy recovered, as they would be able to increase output swiftly and smoothly. Companies that noticeably failed to protect their workforces were quickly identified in the media.

Hence, Covid-19 may have played the role of a catalyst and accelerated the pre-crisis trend of investors taking human capital management increasingly into account when assessing the value of a company.

Resources:

1 Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), “Human capital theory, assessing the evidence for the value and importance of people to organisational success”, 2017.

https://www.cipd.co.uk/Images/human-capital-theory-assessing-the-evidence_tcm18-22292.pdf

2 Institutions have been defined as: “rules, regulations, laws and policies that affect economic incentives and thus the incentives to invest in technology, physical capital and human capital.” Daron Acemoglu, “Introduction to Modern Economic Growth”, Department of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2007. https://www.theigc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/acemoglu-2007.pdf

3 Ibid.

4 Patrick Ngulube, “Handbook of Research on Theoretical Perspectives on Indigenous Knowledge Systems in Developing Countries”, University of South Africa, 2016.

https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/indigenous-knowledges-and-knowledge-codification-in-the-knowledge-economy/16327

5 Ocean Tomo, “LLC intangible asset market value study”, 2020.

6 Ibid.

7 Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google.

8 Investor Responsibility Research Centre Institute (IRRCi), “The Materiality of Human Capital to Corporate Financial Performance”, 2015. https://lwp.law.harvard.edu/files/lwp/files/final_human_capital_ materiality_april_23_2015.pdf

9 Interfaith Centre for Corporate Responsibility (ICCR), “Investor statement on coronavirus response”, 2020. https://www.iccr.org/sites/default/files/page_attachments/investor_statement_on_coronavirus_ response_04.02.2020.pdf

Ref:82521eb

DISCLAIMER

By necessity, this briefing can only provide a short overview and it is essential to seek professional advice before applying the contents of this article. This briefing does not constitute advice nor a recommendation relating to the acquisition or disposal of investments. No responsibility can be taken for any loss arising from action taken or refrained from on the basis of this publication. Details correct at time of writing.

Smith & Williamson LLP

Regulated by the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales for a range of investment business activities.

Smith & Williamson LLP is a member of Nexia International, a leading, global network of independent accounting and consulting firms. Please see https://nexia.com/member-firm-disclaimer/ for further details.

Smith & Williamson LLP is part of the Tilney Smith & Williamson group.

Registered in England No. OC 369631.

Disclaimer

This article was previously published on Smith & Williamson prior to the launch of Evelyn Partners.