“Japanification” fears of the US are misplaced

The fear of ‘Japanification’ – decades of subdued economic growth and sporadic periods of deflation - has stalked policymakers across the world, ever since Japan’s vast financial bubble burst in the early 1990s. Other economies, both developed and emerging have been alert to signs of a similar phenomenon and it is arguably the experience of Japan that has helped drive the vast monetary and fiscal stimulus packages in recent years. But how great a risk is a Japanification of the US economy today?

The fear of ‘Japanification’ – decades of subdued economic growth and sporadic periods of deflation - has stalked policymakers across the world, ever since Japan’s vast financial bubble burst in the early 1990s. Other economies, both developed and emerging have been alert to signs of a similar phenomenon and it is arguably the experience of Japan that has helped drive the vast monetary and fiscal stimulus packages in recent years. But how great a risk is a Japanification of the US economy today?

Certainly, there are similarities. Notwithstanding huge economic stimulus over the past year, US growth has been unexciting for some time. Between the end of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 and the start of Covid in early 2020, the US economy grew by an average of 2.2%1, the weakest rate in the modern era. The risk is that the longer stimulus measures remain in place, the longer the ‘Darwinist’ impulse of capitalism is delayed. Weak companies that should have failed limp on, slowing growth in the broader economy. Entitlement spending may create false economic incentives and dent productivity.

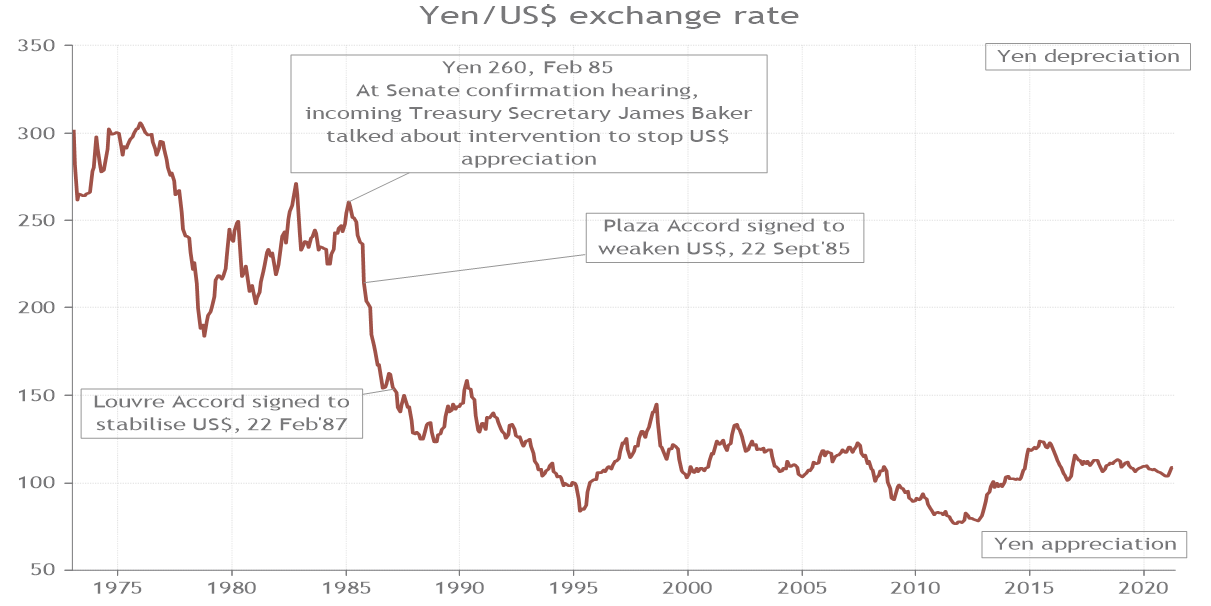

However, as we see it, there are number of important differences between the Japan of the 1980s and the US today. The most important is probably a series of policy errors that were implemented by the Japanese authorities, including how they responded to exchange rate movements. Indeed, the seeds of “Japanification” were sown in early 19852when the yen began to appreciate sharply relative to the US dollar. This came about during the second Reagan Administration, when a major change was made to exchange rate policy to weaken the greenback after its prior sharp appreciation.

Arguably, the turning point for a weaker dollar was the early 1985 Senate confirmation hearings of the incoming Treasury Secretary, James Baker, who stated that the US government’s previous stance against intervention was “something that should be looked at.” The yen appreciated by 22% against the US dollar in 1985 and a further 41% by the end of that decade (Chart 1).

Chart 1: The seeds of “Japanification” were sown in early 1985 when the yen began to appreciate sharply

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, Data as at 21/05/2021

Japanese policymakers sought to address yen appreciation by boosting domestic consumption. In doing so, they let monetary supply get out of control, leading to the now-familiar asset boom. This saw the Japanese stock market and real estate move into bubble territory. The boom also spread into the banking system. By the end of the Japanese economic expansion the banking system was highly leveraged, fuelled in part by an extraordinary housing bubble that saw Tokyo’s Imperial Palace worth more than all the real estate in California3. Japan’s bank loans to GDP were more than 100%4. When the financial bubble burst, asset price declines undermined bank balance sheets and there were significant loan write-offs. This contributed to sub-par growth and deflation for decades.

It didn’t help that the Bank of Japan failed to recognise the severity of the situation and began to raise interest rates in 1989, making a bad situation worse. There were also a number of unfortunate taxation decisions. To address a growing budget deficit, the government of the time, under PM Hashimoto, raised the consumption tax in 1997. This was an ill-timed attempt to balance the books when economic growth was slowing. These policy errors only really started to unwind when Shinzo Abe came to power for the second time in 2012 and unleashed “Abenomics”, a series of economic policies that encompassed fiscal spending, monetary easing and reforms to make Japan more competitive. Prior to that, at no point did Japan attempt the kind of co-ordinated fiscal and monetary stimulus now adopted across the globe.

While it is not impossible that the Federal Reserve makes a mistake, it is likely to be on the opposite side (i.e. too stimulative). A key macro risk is that the longer the Fed continues to run loose monetary policy, the more difficult it may be to control inflation and longer-term interest rates. Given that US equity valuations have been driven to high levels by easy money policy, a sharp reversal to a higher interest rate environment could lead to a correction in stock prices. However, for now, it seems unlikely that the Federal Reserve is going to raise rates any time soon and. In fact, the policy of ‘average inflation targeting’, introduced in September 2020, makes it more possible that the Fed lets the economy run hot than turn cold.

The US is on more solid economic ground than 1990s Japan

Apart from the issues related to potential policy mistakes, structurally, the US financial system and economy differ from in late 1980s Japan. Take US banks: they have been through their nadir during the Global Financial Crisis during 2008 and, for the most part, have sorted out problems of leverage and capital adequacy. Their balance sheets are in good shape, with large capital buffers. According to the IMF, US banks’ core Tier capital, a financial soundness measure of how much capital stands behind lending, was 14.4% in the third quarter of 2020, the highest ratio on record and is up from 10.1% at the start of 20095. Looking forward, banks are in a strong position to support businesses and consumers looking forward.

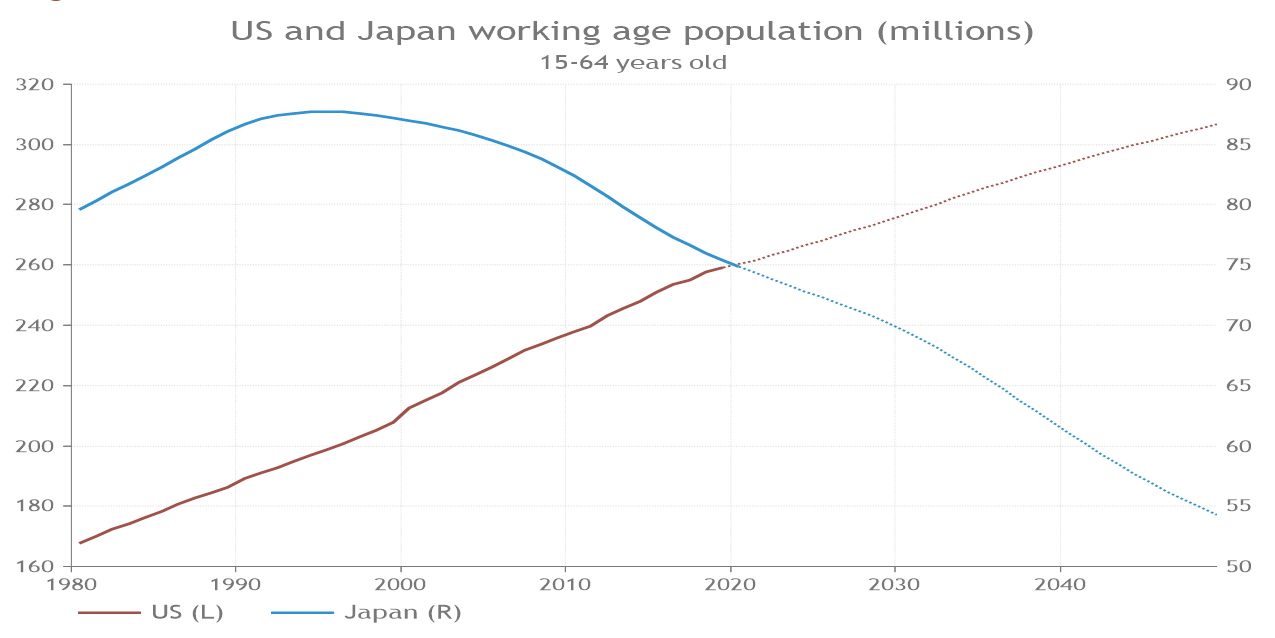

The demographic profile also favours the US long term economic outlook (chart 2). According to Oxford Economics, the US working age population (15-64 years old) is expected to grow by 0.7% per annum up to 2049, one of the highest rates in the developed world6. There is also the potential for population to expand on the surprise. The Biden Administration advocates a more ‘open door’ policy with regards to easing immigration into the US. In contrast, Japan has long struggled with a shrinking working age population, making it difficult to produce long term productivity gains. Low birth rates and limited immigration have conspired to create a demographic crisis in Japan.

Chart 2: Unlike Japan, the US working age population is projected to expand over the long term

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, Data as at 21/05/2021

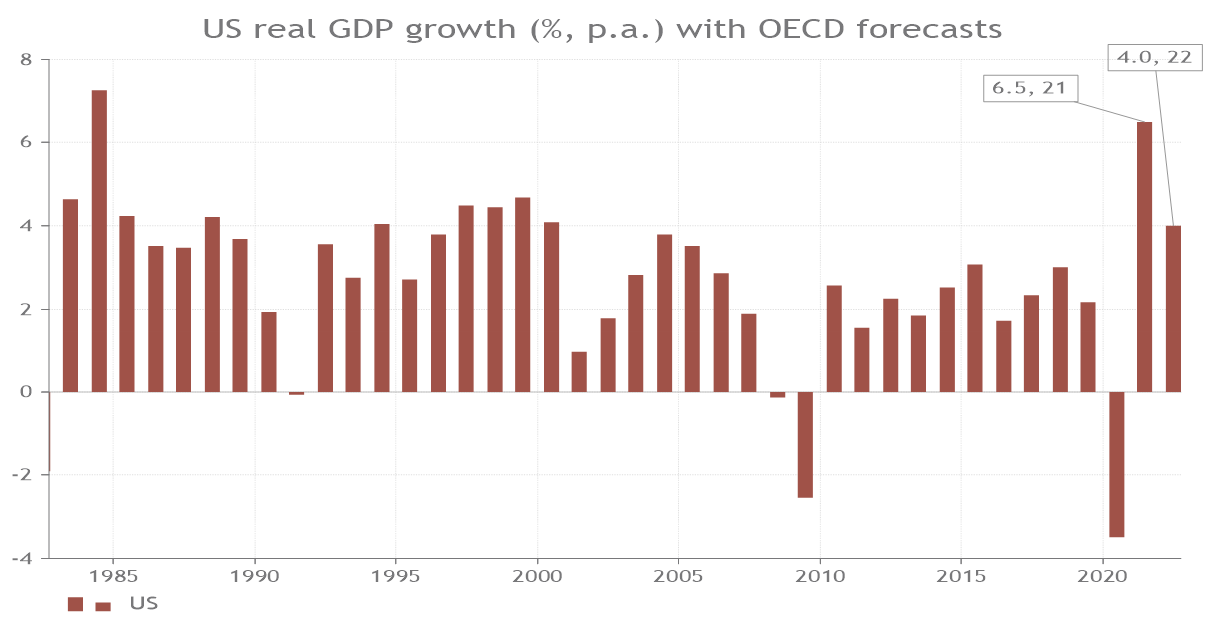

Given the relative health of its banking system and demographic profile, the US economy is in far better health, with growth coming through strongly in the wake of the pandemic. The OECD is predicting US real GDP growth over around 6.5% for 2021 and an also strong 4.0% in 2022 (chart 3). This is supported by a bounce-back for the all-important US consumer, who is supported by government stimulus cheques, job creation, rising household aggregate wealth and opening-up from lockdowns. This doesn’t suggest ‘Japanification’ to us, but instead, a country on the verge of a strong recovery.

Chart 3: Expect a constructive near-term outlook for the US economy

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, Data as at 21/05/2021

Certainly, the US economic and financial market outlook doesn’t come without risks. US corporate debt levels are relatively high, but private sector debt (including households) at 162% of GDP is still around 60% points of GDP lower than Japan at its peak7. Moreover, US non-financial corporates and households, in aggregate, are highly liquid, with plenty of cash on their balance sheet to deal with short term demands for money.

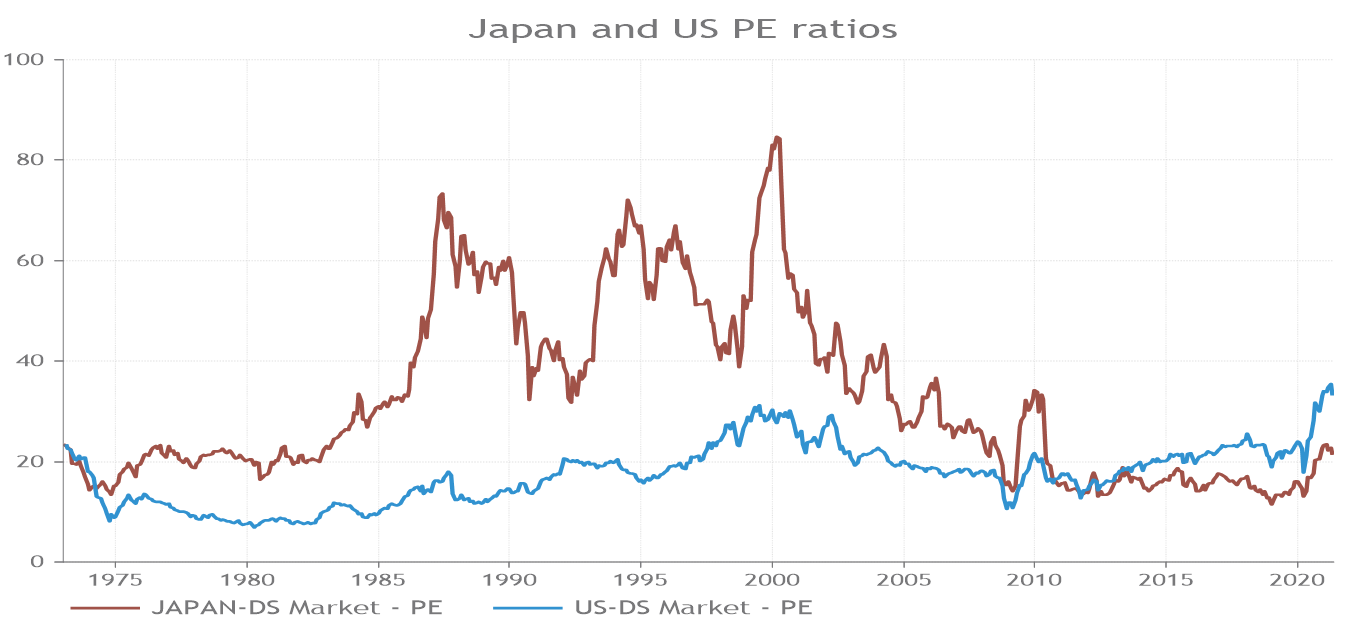

A final consideration is that even if the US equity market feels expensive, it is nowhere near the levels seen in the Japanese market at the height of its bubble. The Japanese market peaked at Price-to-Earnings (PE) ratios of over 80x in the late 1990s compared to around 35x for the US market today (chart 4). There may be plenty for investors to be nervous about today, but Japanification of the US doesn’t need to be one of them. The investment message from the constructive fundamental growth environment is that US stocks have further to rally.

Chart 4: US equity valuations are not as extreme as they were for Japan in the late 1980s-2010s

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP, Data as at 21/05/2021

Sources:

1,2,4,5,6,7 Refinitiv, Smith and Williamson

3 https://www.scmp.com/magazines/style/news-trends/article/3091222/japan-1980s-when-tokyos-imperial-palace-was-worth-more

DISCLAIMER

By necessity, this briefing can only provide a short overview and it is essential to seek professional advice before applying the contents of this article. This briefing does not constitute advice nor a recommendation relating to the acquisition or disposal of investments. No responsibility can be taken for any loss arising from action taken or refrained from on the basis of this publication. Details correct at time of writing.

RISK WARNING

Capital at risk. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the original amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. Further information is available in the Key Investor Information Document (KIID), the risk section of the Fund’s prospectus and the Fund Factsheet. Please read the KIID before making any investment decision.

Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP

Authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.

Registered in England No. OC 369632. FRN: 580531

Smith & Williamson Investment Management LLP is part of the Tilney Smith & Williamson group.

© Tilney Smith & Williamson Limited 2021

Disclaimer

This article was previously published on Smith & Williamson prior to the launch of Evelyn Partners.